Vector Processing

Hardware compute platforms have been evolving at an expeditious rate, resulting from drastic improvements in CPU frequencies, memory bandwidth, and capacity enhancements across the memory hierarchy, the development of feature-rich ISAs (Instruction Set Architecture) with native hardware support for increasingly complex operations, shrinking of the transistors and microprocessors, availability of multiple cores and CPUs and so on. The availability of these highly capable compute-intensive platforms, coupled with their ever-expanding range of supported features and available resources as part of affordable COTS (Commercial-Off-The-Shelf) Servers, has opened up a treasure trove of possible use cases and limitless applications that were previously both unheard-of and unexplored.

The philosophy of SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) and Vector Processing is one such driving technology that has gained particular traction due to the advancements and diversification of computational forms. The clock speed improvements in the last decade have plateaued as the sharp escalation in power consumption and heat production resulting from the increase in clock speed makes it infeasible to practically improve the CPU frequency without hitting the thermal and power limits. Consequently, there has been a shift to using parallelism with the increased number of cores and parallelism at the register level to extract more performance, resulting in the evolution and adaptation of SIMD. This was brought to the forefront by the development of GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) and their widespread applications for Graphics Rendering, Image Processing, and AI workloads. Extending this concept of Vector Processing to make it generic for a wide variety of supported operations and to make it ubiquitous by providing this support as part of general-purpose CPUs, various computational architectures have incorporated vector engines as part of their native hardware and have provided an extensive feature-rich ISA that exploits these vectorization capabilities on general-purpose CPUs. SIMD and Vector processing as part of general-purpose CPUs is particularly attractive as they are very cost-effective compared to GPUs, which are intended to be used as additional accelerators, thereby increasing the capex and opex.

So, what is SIMD and Vector Processing, and what’s the fuss all about? Broadly speaking, SIMD follows the paradigm of data parallelism wherein a single instruction or operation is performed on multiple data streams simultaneously by utilizing multiple processing elements available as part of the underlying hardware. Vector Processing adheres to this ideology of SIMD by utilizing vector engines and vector instructions supported by the ISA. Let’s explore this through an example:

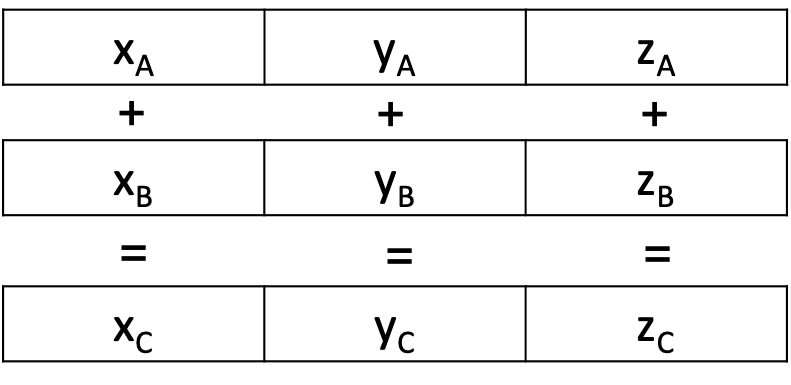

Let’s consider an example where we have to perform the addition of two vectors (A and B) in the 3-dimensional coordinate system, each having the x, y, and z coordinates.

A = [xA, yA, zA], B = [xB, yB, zB]

Let C = [xC, yC, zC] represent the sum of the two vectors A and B.

The conventional way of doing this would be to use three separate Add instructions as follows:

xC = xA + xB

yC = yA + yB

zC = zA + zB

Vector Processing uses SIMD at a register level by packing these scalars into a single vector register and uses just one Add instruction as follows:

The use of a single Vector Add instruction natively supported by the hardware will substantially augment the performance due to the reduced CPI as compared to three separate scalar Add instructions. The contemporary method of improving the performance would be to use multiple cores and realize data parallelism by distributing the data to be added across the multiple cores. In this case, three separate cores can be used to perform the addition of the x components, y components, and z components, respectively. However, the use of multiple cores can result in increased power consumption compared to vector processing, which is an elegant and efficient solution.

The two major computing platforms, namely Intel and ARM, have iterated through different generations of SIMD and vector processing support, providing a wide (pun intended) variety of features as part of their ISA.

Intel’s evolution of SIMD

The dawn of Intel’s exploration into SIMD for x86 architecture began with MMX (interestingly, a meaningless initialism) in 1997, providing support for eight vector registers of length 64 bits each. These registers could either be used to hold 64-bit integers or used as vectors storing integers in a packed format (two 32-bit, four 16-bit, or eight 8-bit integers). SSE (Streaming SIMD Extension) was the next generation of SIMD support that introduced wider vector registers of 128-bits that could support both floating-point numbers and integers. AVX (Advanced Vector Extensions) and AVX2 were the next iteration that provided support for 256-bit vectors. The latest generation, AVX-512, is a very mature and established version for vector processing, supporting up to 512-bit vectors, and it consists of multiple instruction subsets with diverse ISA support for different target applications.

ARM’s evolution of SIMD

ARM adheres to the philosophy of RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Architecture), where the cycles per instruction is minimized at the cost of increasing the number of instructions in the program, which is antithetical to the concepts of CISC (Complex Instruction Set Architecture) followed by Intel. Thereby, ARM uses only fixed-size instructions to support even the new instructions for SIMD, resulting in significantly reduced power consumption.

ARM’s journey into SIMD commenced with Neon, which supports fixed-length vectors of 128 bits with comprehensive support for both integers and floating-point numbers. With the introduction of SVE (Scalable Vector Extensions), ARM presented a new philosophy of working with a vector-length agnostic ISA that abstracted away the details of the hardware vector length with the use of predicates (which are essentially bitmasks representing the active/inactive nature of the vector lanes). The vector registers provided as part of the underlying hardware could be any multiple of 128, all the way up to 2048 bits, thereby providing immense scope for parallelism at the register level while also enabling increased flexibility due to the vector-length agnostic behavior. This instruction and feature support has been further expanded with the introduction of SVE2.

What does it mean for us?

The growth and establishment of Vector Processing as a technology and its widespread availability as part of COTS presents an exceptional opportunity to augment the performance of our applications. In this direction, an effortless and uncomplicated starting point to vectorize our applications would be to leverage the clever capabilities of modern-day compilers. Most prevalent compilers include some form of auto-vectorization at optimization levels of O2 and above. Further, compiler directives for vectorization could be added at strategic points in our application to direct and aid the auto-vectorization functionality of the compilers. Although auto-vectorization by compilers could result in considerable performance gains, a fundamental re-think at the algorithm level might be required to exploit all the vectorization capabilities of the underlying hardware efficiently and effectively. In this regard, the different computational architectures support manual vectorization by providing intrinsics as part of their libraries, which are essentially high-level function calls that get mapped to the corresponding assembly instructions.

Conclusion

The support for SIMD continues to evolve and take more advanced forms, with Intel’s AMX (Advanced Matrix Extensions) and ARM’s SME (Scalable Matrix Extension) as the newest entrants to the SIMD family. AMX introduces 2-dimensional registers called tiles to aid a variety of matrix operations. SME builds on SVE and SVE2, adding new capabilities to efficiently process matrices with features like matrix tile storage, on-the-fly transposition, the ability to compute the outer product of SVE Vectors, etc.

The rise of transformative and pervasive technology like Virtualization, Cloud Computing, and Generative AI provides exciting opportunities to utilize the increased computing capability and ever-expanding features of SIMD and Vector Processing. Developing algorithms in a SIMD-compliant manner can substantially benefit applications without requiring additional hardware like accelerators. Thus, I firmly believe that SIMD and vector processing can be powerful tools with the potential to enhance the performance of applications drastically and, more importantly, feasibly.